By Krista Halling DVM DACVS

When dogpacking, your dog’s paws are the most frequent point of contact with every rock, root, and ridge. They serve as the primary interface between your dog’s body and the terrain beneath, yet paw health is often overlooked or misunderstood. Here’s a deep dive into paw anatomy and footpad care for your best buddy.

Paw Pad Anatomy and Function

A dog’s paw is not just a furry hand—it’s a biomechanical masterpiece. Beyond just skin and padding, a dog’s paw is a high-functioning structure that supports, protects, and powers movement over varied terrain.

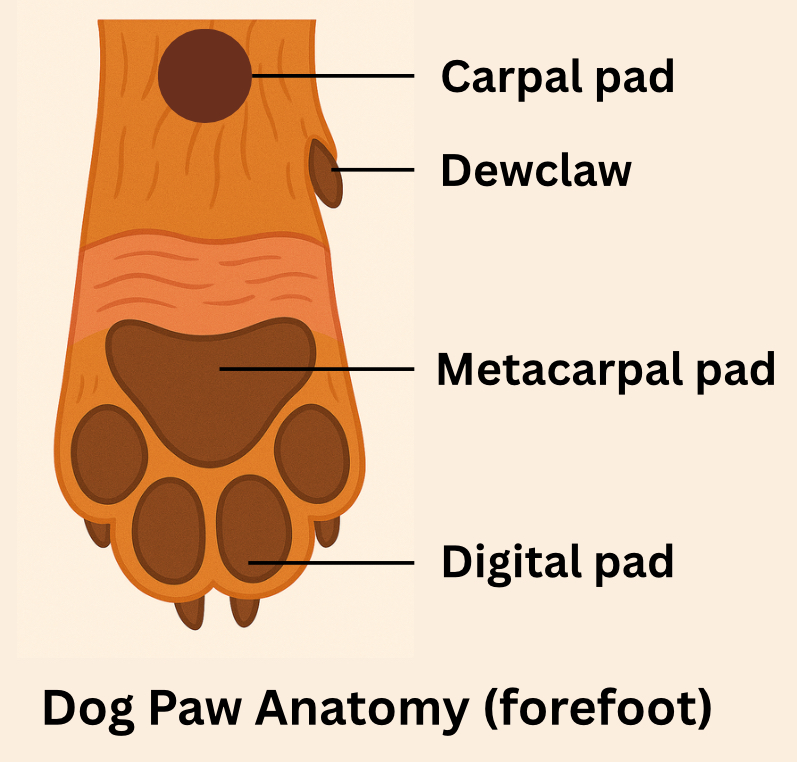

Structural Anatomy

- Digital pads: Found under each toe, these absorb shock, provide traction, and help distribute load during movement.

- Metacarpal/metatarsal pad: The large central pad bears the majority of the body’s weight and absorbs impact during running or landing.

- Carpal pad: Located on the front limbs, this pad aids in braking, turning, and downhill control.

- Dewclaws: Often misunderstood, these can help stabilize the limb during agility maneuvers and may reduce torque on the wrist joint in turns or descents (Zink & Van Dyke, 2013).

Protective and Sensory Functions

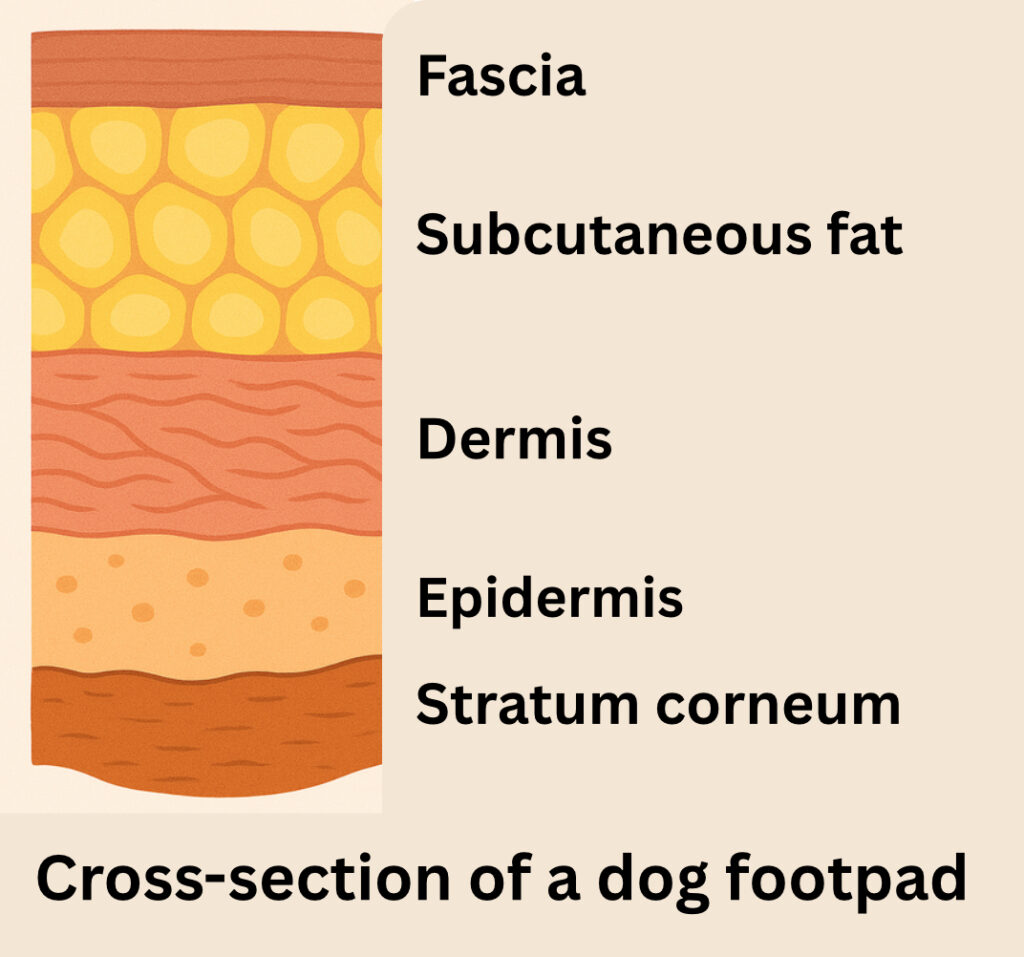

Paw pads consist of a thick keratinized outer layer and an underlying cushion of fat and connective tissue. This structure acts as a shock absorber and provides insulation from rough or cold surfaces (Dowling & Lagutchik, 2016). Pads also contain sweat glands and dense sensory receptors that support thermoregulation and proprioception—your dog’s awareness of limb placement and terrain.

Conditioning Paws for the Trail

Dogs aren’t born with trail-ready feet. Just like humans develop calluses or muscular endurance for hiking, dogs need to gradually condition their pads and supporting structures.

Keratin Buildup and Surface Exposure

Controlled exposure to mildly abrasive terrain leads to thickening of the pad’s outer layer. Conditioning should begin with relatively soft terrain (such as grass then dirt trails) before progressing to packed sand, small gravel, or compact rocky trails. Sudden overexposure can result in abrasions or pad tearing (Zink, 2008).

Impact of Various Surfaces on Footpad Conditioning

- Grass or dirt trails: Low (grass) or low-to-moderate (dirt roads, trails) abrasion, ideal for beginners

- Packed sand or soft gravel: Medium to high abrasion, builds footpad toughness; cautious in hot weather—sand gets very hot!

- Pea gravel or soft sand: Improves proprioception and strengthens intrinsic paw muscles

- Asphalt: High-impact so increase duration very slowly and avoid during hot weather

Neurological and Physical Benefits

Conditioning strengthens not only the skin but the digital flexors, ligaments, and tendons. Dogs also develop better terrain awareness and proprioception, helping them navigate technical trails with more confidence (King et al., 2022).

Barefoot or Booties?

Many dogs do best barefoot. Their paws evolved to handle varied terrain—and going without booties enhances traction, proprioception, and muscle engagement. But there are times when added protection is a smart choice.

When Barefoot Is Best

- Natural terrain: forest floors, packed trails, dry grass

- Dogs with healthy, conditioned pads

- Mild or cool temperatures

- Terrain requiring grip and agility

When to Use Booties

- TOO HOT: Hot pavement or sand: Surfaces can burn within minutes

- TOO COLD: Snow, ice, or salted roads: Prevents frostbite and chemical irritation

- TOO SHARP: Sharp terrain: Drainage stones, lava rock, scree, shale, or cactus zones

- WOUNDED or UNTRAINED: Healing footpad injuries or paws that haven’t been conditioned for the expected terrain and distance (best to prevent that situation rather than apply booties for a long duration)

Booties should be breathable, well-fitted, and tested at home before use. Dogs require training to tolerate booties comfortably. Sudden use without practice can cause gait changes or distress (King et al., 2022).

Paw Wax vs Paw Balm: What’s the Difference?

Paw Wax

Paw wax (like Musher’s Secret) forms a protective, semi-occlusive layer over the pads. It’s ideal for shielding against ice, snow, and salt during cold-weather outings.

- Best used before exposure

- Wears off over distance or wet conditions

- Cautious if using in hot environments—it may soften pads and increase friction risk (Morgan, 2019)

Paw Balm

Balms are formulated to hydrate and heal. They contain ingredients like shea butter, coconut oil, and beeswax to soothe dry or cracked pads.

- Best used after activity or overnight

- Avoid petroleum-based products—they may irritate or be toxic if ingested

- Great for dogs in dry climates or those with chronic pad issues

Tip: Apply balm before bedtime to reduce licking and allow full absorption.

Monitoring for Paw Injuries

Common Trail Injuries

Even well-conditioned paws can suffer trauma—especially on rough, hot, or unfamiliar terrain. Spotting issues early can prevent minor injuries from becoming serious problems.

- Abrasions: Caused by friction from sand, shale, or rough ground

- Maceration injuries: Caused by soft wet footpads running on abrasive surfaces

- Burns: Occur on hot pavement or sand; surfaces over 125°F (51°C) can burn within 60 seconds (Peterson, 2016)

- Cracked pads: Caused by dryness, repetitive impact, or cold weather

- Punctures or lacerations: From sharp stones, sticks, or thorns

- Foreign bodies: Grass awns, burrs, cactus spines, or small stones lodged between toes or pads

Signs to Watch For

Many dogs won’t show discomfort right away due to adrenaline and excitement. Always check paws during breaks, and do a full inspection after your outing (Hewitt-Dugdale et al., 2021).

- Limping or reluctance to walk

- Licking or chewing feet

- Broken or torn nails

- Darkened pads, visible cracks, wounds or bleeding

- Flinching during paw checks

First Aid Tips

- Rinse with saline or clean water

- Gently dry and inspect

- Apply paw balm if cracked or dry

- Use vet wrap (applied loosely) or a clean bootie to protect wounds until you get home

- Avoid alcohol or hydrogen peroxide—they delay healing

- Footpads bleed A LOT when cut—veterinary care is almost always needed in this case

- Contact your veterinarian to ask if your dog’s foot should be seen

Tips for Trail-Ready Paws

- Trim nails: Long nails change foot posture and increase torque on paw pads

- Trim hair between toes: Reduces buildup of ice and abrasive dirt (keep it just short enough that it isn’t matting or collecting dirt and ice)

- Gradually condition your dog’s paws to the desired terrain

- Rest regularly: Give feet a break every hour or two on long outings

- Hydrate often: Dehydrated tissues are more prone to damage

- Watch the heat: If the pavement or sand feels hot to your hand, it’s too hot for paws

- Don’t let your dog run on concrete after swimming: pads will likely be too soft and will tear easily

- Trail bag essentials: vet wrap, tick remover, bootie or baby sock, paw balm, tweezers, raw honey

Your dog’s paws are incredible—they’re the foundation of every adventure. With regular conditioning, thoughtful terrain choices, and a little preventive care, your dog can explore longer, recover faster, and move more confidently. Whether barefoot or booted, balm-coated or au naturel, the best paw care is proactive for ensuring your dog has happy, healthy feet.

About the author

Krista Halling is a veterinarian board-certified with the American College of Veterinary Surgeons and creator of Dogpacking.com. She is also certified in the Human-Animal Bond and in Canine Physical Rehabilitation. Krista loves travelling and adventuring with River, her mini goldendoodle sidekick.

References

- Dowling, P. M., & Lagutchik, M. S. (2016). Thermoregulation: Physiology and Clinical Implications. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 46(5), 785–797.

- Hewitt-Dugdale, A., et al. (2021). Pain assessment in dogs: How do we know what they’re feeling? Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 43, 11–19.

- King, M. R., von Heimendahl, A., & Weller, R. (2022). Effect of protective footwear on gait in working dogs. Veterinary and Comparative Orthopaedics and Traumatology, 35(1), 33–40.

- Morgan, D. M. (2019). Paw pad dermatoses in dogs: Etiology and management. Today’s Veterinary Practice, 9(2), 34–41.

- Peterson, C. (2016). The Effect of Surface Temperature on Canine Paws: A Summer Study. Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care, 26(4), 514–518.

- Zink, M. C. (2008). Peak Performance: Coaching the Canine Athlete. Canine Sports Productions.

- Zink, M. C., & Van Dyke, J. B. (2013). Canine Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation. Wiley-Blackwell.

Leave a Reply